Boomtownlinking past & present

Welcome to my passion project: writing about people, places, and ideas from the past that echo in the present. |

|

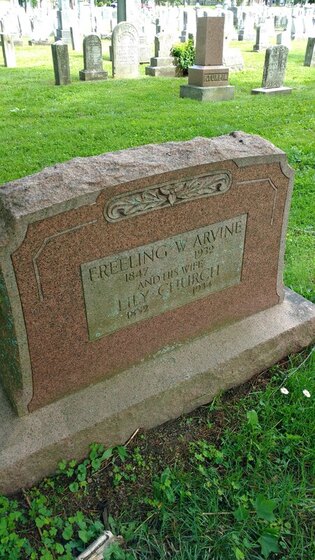

More than 300,000 people have been laid to rest in Mount Hope Cemetery since it opened in 1838. Some of them are internationally famous—Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass—and people come from far away to pay their respects. I walk in Mount Hope a lot. I stop at Anthony’s and Douglass’ graves sometimes, but I admit: I’m more curious about people whose stories went silent when they died. And I’m not the only one. It seems every day there is news about another unlikely inventor, film director, or business person, usually a woman, whose accomplishments were forgotten after she was gone. There’s a woman buried in the cemetery I’ve been curious about for a long time. Her name was Lily J. Church Arvine. I ran across her name while researching the history of a house I lived in. The house is on Mt. Vernon Avenue near Highland Hospital. It’s part of the Ellwanger & Barry Tract, built on former nursery land. One of the documents related to the 1906 construction of the house listed her as the contractor. It struck me as unusual that a woman would be involved in the real estate development business in 1906, particularly as a contractor. But I really don’t know if it was. Maybe there were lots of them. Has anyone ever really looked into it? I poked around online. Arvine was born in 1852, the youngest of three daughters in a well-off Rochester family. Her mother was Elizabeth Grant Church, born in Canada. Her father, Sidney Church, was a rope manufacturer who came to Rochester from Connecticut. Arvine married Freeling Arvine when she was in her 40s and established in her business. He was a scientist and inventor who perfected a process for using gasoline—once just a byproduct of crude-oil refining—as a fuel. Later he joined her in real estate. When Sidney Church died he left his youngest daughter two acres of land between West Avenue and Clifton Street. Starting around 1891, Arvine successfully developed it into Churchlea Place, a middle-class neighborhood that attracted staff of the nearby St. Mary’s Hospital and businessmen from Bull’s Head. She and her mother lived at No. 1. The street is now partially redeveloped as part of the hospital campus, but some of the original houses remain. Her obituary described her as an extensive real estate developer on the city’s west side. With the profits she made on Churchlea Place, Arvine went on to build homes on Algonquin Terrace, Child and Wooden Streets, and several streets near Ritter Dental Works on West Avenue. She also developed the Arvine Park Tract, three streets off Genesee Park Boulevard near Elmwood Avenue. Arvine picked locations primed for growth; this one was near the new University of Rochester River Campus and Genesee Valley Park. One of the streets, Arvine Heights, is a National Historic District listed in the National Register. Many homes on the street retain their original Bungalow, Dutch Colonial Revival and Colonial Revival characteristics popular in the 1920s. Homes built at that time in many Rochester neighborhoods had deed stipulations preventing African Americans from living there. It’s likely that Arvine’s middle-class neighborhoods were among them, and I’m going to dig a little more to find out. “Restricted” was the code word used to describe this discriminating practice. It was not illegal, but it has had terrible repercussions for the Rochester region that continue to this day. I don’t know, yet, how Arvine became the contractor for the house I lived in. Did she know the Blackalls, the family who had it built? Did she have an arrangement with Ellwanger & Barry Realty Co., which was developing the area? Arvine retired in 1929. When she died in 1934 she left an estate of $10,000, about $180,000 in today’s dollars. Half of it went to her niece, Sarah Caldwell, and the other half went to her longtime housekeeper, Sadie MacPhee. By the way, years after I learned about Arvine I just happened upon her grave on one of my walks in Mount Hope. She is buried next to her husband and her parents. Sources: City of Rochester Historic Resources Survey 2000, cityofrochester.gov Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, 18 Jan 1934, fultonhistory.com

2 Comments

I spent some time researching my Sicilian ancestors today. This is my grandmother, Sara Mazza Parker, my namesake. Born in 1907, first-generation. A teacher saw her potential and encouraged Grandma's old-country parents to let her go to college. She was a Cornell and Middlebury graduate, master's degree, teacher. We can say it's the classic American immigrant success story. But we can't forget the other classic American story: immigrants as dirty, dangerous, ignorant. This has always been with us. I learned 11 Sicilians were lynched in New Orleans on one gruesome March day in 1891. There were many more incidents of violence and exclusion in cities where Sicilians settled. Italians from the mainland distanced themselves from the poor, illiterate peasants from Sicily. My great-grandfather knew no English of course when he came to the States on April 4, 1904. He was a fisherman from Brucoli. He settled in Oakfield, Genesee County, New York, joining his older brother, Sebastiano, and worked in the gypsum mines. He sent for his wife, Maria Bucceri Mazza, from Sortino, a few years later. She came with their two young children, my grandmother's older sister Francesca and brother Pietro (Aunt Fran and Uncle Peter to me). It would be generations before Sicilians found their place in mainstream American society. My grandma would have grown up hearing those stories. No wonder she changed her name from Santina to Sara and married a Yankee. That is a story for another day. I wish I'd asked more about her early life when she was alive. I would have asked her about this. |

Details

AuthorThese are stories of people, places and events of the past that seem to jump out at me. Maybe they've been waiting for someone to tell them! Archives

July 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed