Boomtownlinking past & present

Welcome to my passion project: writing about people, places, and ideas from the past that echo in the present. |

|

Big statues honoring powerful men are all the rage these days. Literally. They’re being toppled and beheaded and thrown into rivers and slathered in rainbows of graffiti as symbols of racial injustice. This reminded me of something Rochester abolitionist Sarah Blackall told Frederick Douglass in a letter in 1893. Her husband was traveling for work in the South and had run across a monument to Henry Clay in New Orleans. Clay was a career politician from Kentucky in the first half of the 19th century. He was a statesman’s statesman: a House speaker, a senator, and secretary of state under John Quincy Adams. He architected big compromises to stave off civil war. Some of this revolved around the issue of slavery. Clay opposed it as a system and argued for gradual emancipation. However—before you get all ‘yay, Clay’—he still viewed slaves as legal property, and he owned slaves himself. (I know.) When he was secretary of state and living in Decatur House in Washington, D.C., one of his slaves, Charlotte DuPuy, sued him in 1829 to win her freedom, saying her previous owner had promised her emancipation and that it should have carried over to Clay when he bought her. While the suit was pending, Clay’s term ended and he returned to Kentucky, taking DuPuy’s husband and daughter with him. In the gray area between slavery and freedom, DuPuy stayed at Decatur House for a year and a half and worked for pay for Clay’s successor, Martin Van Buren, awaiting the outcome. She lost. And if that weren’t bad enough, when she refused to move back to Kentucky (naturally, why would she after a taste of freedom?), Clay approved her removal to jail and then sent her to New Orleans to work for relatives. She didn’t see her family for another 11 years, when Clay granted her freedom. In her letter to Frederick Douglass, Sarah paraphrased the inscription on the base of Clay’s memorial: “‘If I could be instrumental in eradicating the great stain, slavery, from the character of our country, I would not exchange the proud satisfaction which I should enjoy for all the triumphs ever decreed to the most successful (conquerors).’ “Perhaps you have seen the statue,” she wrote. “It struck me as being a strange sentiment for a slave owner.” That was 127 years ago. I picture Sarah’s husband, Frank, standing at that statue, leaning in to read the inscription. I picture Douglass reading her words and shaking his head. He was well aware of Clay’s inconsistencies. Public outcry over monuments and streets that honor white supremacy is nothing new in New Orleans, and three years ago the city removed several statues. Fast forward to last month when monument protests around the country were heating up. I did a quick scan online and didn't see any new action around the Clay memorial. But I checked again today and sure enough, the demand for its removal, along with others, has reached a crescendo. Here's an idea: Maybe New Orleans should replace it with a tribute to Charlotte Dupuy, one of its own, who stood up to one of the most powerful men in the country to fight for the right to be free.

4 Comments

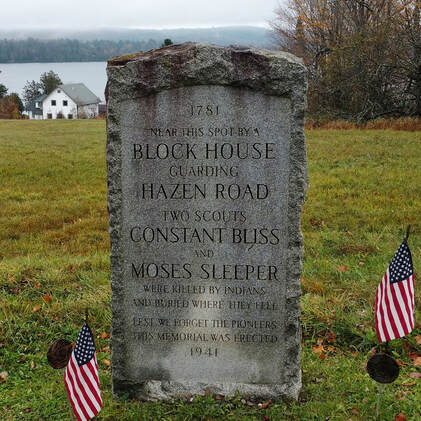

Sometimes when I’m watching a genealogy show, like Finding Your Roots, I am reminded that most people know very little, if anything, about their family tree. I’ve researched mine for 20 years and have come to believe they live on in my DNA. Science has shown that the way our ancestors handled stress, for example, adds information to their DNA that is passed down to future generations. These people are literally part of me. Exploring them is a way to get to know myself. And god knows I’ve spent a lifetime trying to do that. We might find out our forebears lived through some stressful times. But finding out what effect that had on them is not so easy. The details of a person’s life start to disappear the minute they die. So you start with what you do know. You can learn a surprising amount in 10 minutes on a genealogy website. In one branch of my tree there are preachers and teachers. In another, healers and people good with their hands. And farmers. The farmers are all over the place. For most of history, work was just work. It wasn’t like Elias Van Steenburg woke up one day, rolled over and said to his wife, I love vegetables and cows. I think I’ll go into farming. Maybe he did love it; or maybe it was the only way he could keep food on the table. Knowing what work my ancestors did doesn’t tell me much about the kind of people they were. I have to know how they did things—how they loved, conducted business, dealt with the neighbors. Did they like being in charge or punching a time clock? Did they declare their principles or were they more ‘live and let live’? Did they have dreams and goals? What kept them up at night? What really pissed them off and what made them laugh? Does my family laugh the same way today? But we can only know so much, and sadly these details are almost always lost forever. So for instance, if my fourth great-grandfather Moses Sleeper fought for the resistance in the Revolutionary War, I know what side of history he ended up on. But I can’t know what drove that decision unless I understand what was going on in his community (or in his own head, if I strike gold). There are probably valid personal motivations in addition to the political ones we all learn in school. I can’t come to sweeping conclusions about my ancestors based on a few slim facts. Life is complex. And this is where genealogy gets dangerous. If I’m pleased that my ancestor was a patriot and not a loyalist, I can make all kinds of assumptions about his life to paint a rosy picture. I can ignore or simply fail to look for facts that don’t fit that picture. He was wealthy (but a real bastard to his tenants). She earned a Ph.D. (but spent three years in an institution). Lots of people do this about their ancestors. Very simple, one-dimensional snapshots. It probably makes them feel better about themselves. I feel the danger in that too. For me, the lure of family history is the dark stories—deals gone sour, prolonged mournings, mental breakdowns, that sort of thing. And yes, in a way they make me feel better about my life. They show that people have always struggled. Anything I’m going through, millions have been there before me and my pipsqueaky life. Knowing this nudges me to lighten up and make the most of this temporary blip of existence. Even if I don’t fully know them, they are with me, those ancestors. They’re never far. Maybe DNA has something to do with it. Think what you will about spirits or ghosts, but I'm convinced that what we see is not all there is. The more stories I uncover, the more connected I feel. And the better I feel in my own skin. I moved last month from Rochester, NY, where I’d lived for 33 years. I was ready to explore and experience a new place. The process of deciding where that would be took some time, but in the end it brought me to the mid-Hudson Valley of New York.

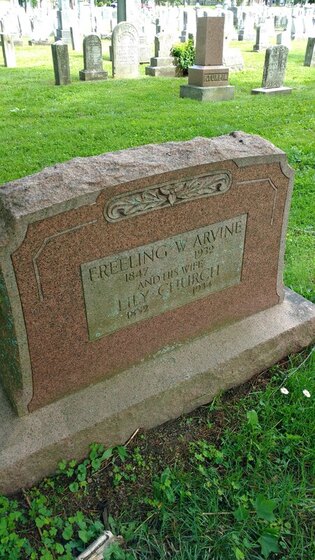

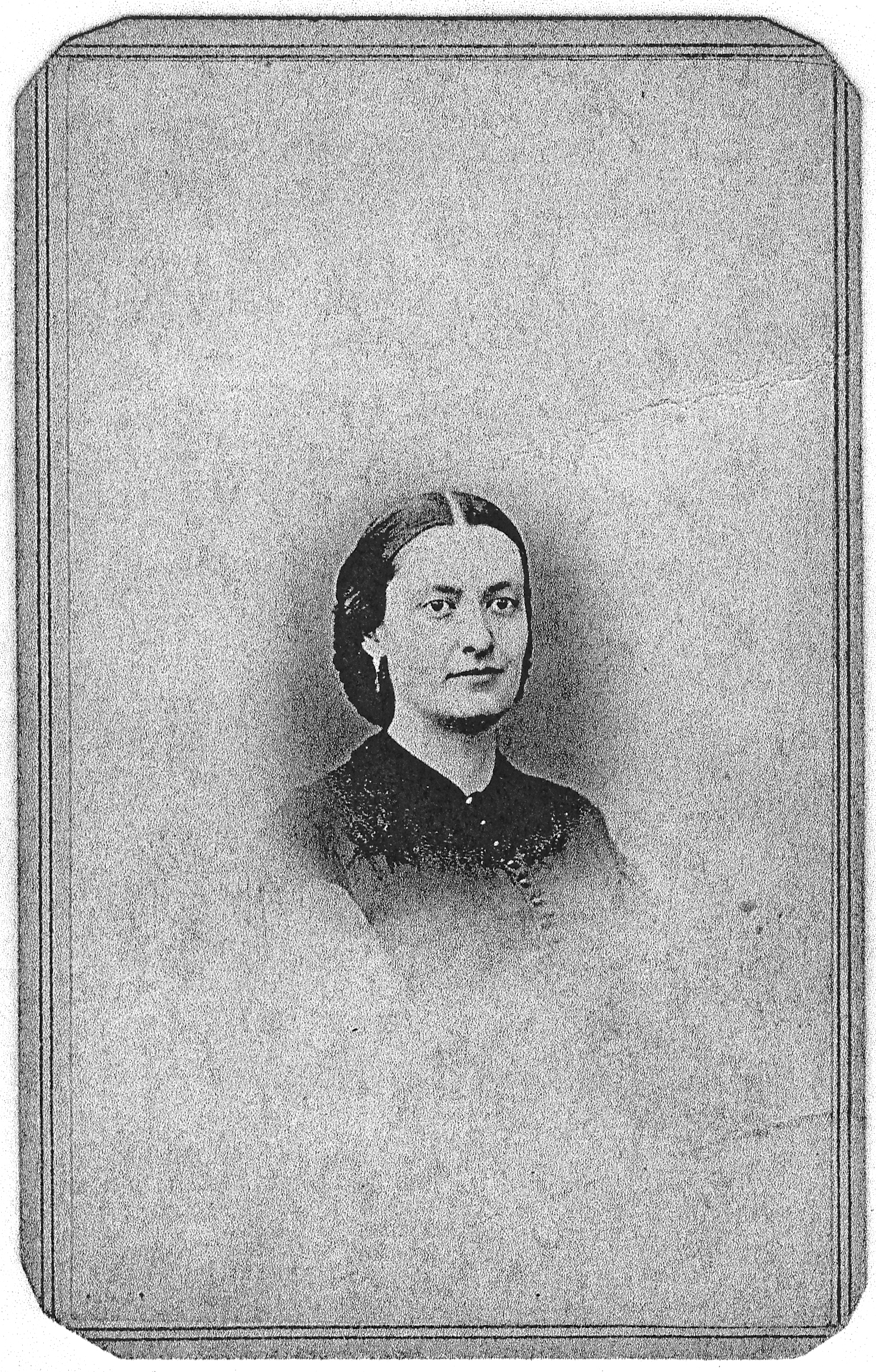

I live in Dutchess County near Hyde Park, of Roosevelt fame. I’ve been visiting friends in the area for years. It’s beautiful—plentiful parks, the mighty Hudson River, quaint towns, and trees, trees, trees. Lately I’ve been wondering if the pull to come here might be in my DNA. A couple years ago I learned of ancestors who were among the first Dutch to live here—nearly 400 years ago. I’m starting to research one in particular, an eighth-great-grandfather named Jan Jansen Van Amersfoort. Jan was a carpenter who helped build the stockade at Wiltwyck, which was renamed Kingston in the 1660s after the British took over. He arrived at the settlement in 1658 from New Amsterdam, now New York City, to which he had sailed as a boy from Amersfoort in the Netherlands. I’d always heard we had Dutch in our family tree. My maternal grandfather’s mother was born a Van Steenburg. Some in our family had wondered how recently they had come to this country. My uncle traced it all the way back to the earliest Dutch settlers. For 40 years the Dutch—not the English—ruled European settlement in this part of New York, Massachusetts, Delaware and Pennsylvania. New York City’s melting-pot reputation has everything to do with the early Dutch presence. There is so much that we didn’t learn in school about early American colonization. Where were the Dutch in all those stories? The more I learned, the more curious I became, and so nearly a year ago I flew to the Netherlands. I spent most of my time in Amsterdam but took a 25-minute train ride to Amersfoort, Jan’s hometown. (That's Amersfoort in the photo above.) Until I was across an ocean, standing on a brick-paved street gazing at a house that looked almost exactly like one I had seen a few months before in the Hudson Valley, the full import of the Dutch influence in early America hadn’t hit me. It was wild to think I was related to those people. Some bit of my DNA had come from that exact dot on the map of Holland. When I got home I did some research. Jan was surprisingly easy to find. Translated Dutch court records preserved in the Ulster County Archives show that, for all of his apparent usefulness as a carpenter, Jan also was a lastpost—a persistent troublemaker. He was arrested 70 times in New Netherland, including for beating his pregnant wife, Catharyn, nearly to death. She and the baby survived. Jan was banished from Wiltwijck and fined 500 guilders. Unfortunately, he didn’t stop. Three years later brought more of the same in a petition by Catharyn: “She is no longer able to keep house with her husband on account of his greatly abusing her every day,” the records state—pushing, beating, chasing, threatening to kill her. This time the court ordered he be sent away on the next ship for a year and six weeks. I will probably never know what was going on with Jan. But Catharyn’s voice is clearly heard in the record—thanks to the more egalitarian ways of the Dutch, however briefly they ruled. No longer is the Hudson Valley simply a charming place to me. It is alive with all the messy moments of people who have come before me. This post is adapted from an essay in Hudson Valley Magazine.  More than 300,000 people have been laid to rest in Mount Hope Cemetery since it opened in 1838. Some of them are internationally famous—Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass—and people come from far away to pay their respects. I walk in Mount Hope a lot. I stop at Anthony’s and Douglass’ graves sometimes, but I admit: I’m more curious about people whose stories went silent when they died. And I’m not the only one. It seems every day there is news about another unlikely inventor, film director, or business person, usually a woman, whose accomplishments were forgotten after she was gone. There’s a woman buried in the cemetery I’ve been curious about for a long time. Her name was Lily J. Church Arvine. I ran across her name while researching the history of a house I lived in. The house is on Mt. Vernon Avenue near Highland Hospital. It’s part of the Ellwanger & Barry Tract, built on former nursery land. One of the documents related to the 1906 construction of the house listed her as the contractor. It struck me as unusual that a woman would be involved in the real estate development business in 1906, particularly as a contractor. But I really don’t know if it was. Maybe there were lots of them. Has anyone ever really looked into it? I poked around online. Arvine was born in 1852, the youngest of three daughters in a well-off Rochester family. Her mother was Elizabeth Grant Church, born in Canada. Her father, Sidney Church, was a rope manufacturer who came to Rochester from Connecticut. Arvine married Freeling Arvine when she was in her 40s and established in her business. He was a scientist and inventor who perfected a process for using gasoline—once just a byproduct of crude-oil refining—as a fuel. Later he joined her in real estate. When Sidney Church died he left his youngest daughter two acres of land between West Avenue and Clifton Street. Starting around 1891, Arvine successfully developed it into Churchlea Place, a middle-class neighborhood that attracted staff of the nearby St. Mary’s Hospital and businessmen from Bull’s Head. She and her mother lived at No. 1. The street is now partially redeveloped as part of the hospital campus, but some of the original houses remain. Her obituary described her as an extensive real estate developer on the city’s west side. With the profits she made on Churchlea Place, Arvine went on to build homes on Algonquin Terrace, Child and Wooden Streets, and several streets near Ritter Dental Works on West Avenue. She also developed the Arvine Park Tract, three streets off Genesee Park Boulevard near Elmwood Avenue. Arvine picked locations primed for growth; this one was near the new University of Rochester River Campus and Genesee Valley Park. One of the streets, Arvine Heights, is a National Historic District listed in the National Register. Many homes on the street retain their original Bungalow, Dutch Colonial Revival and Colonial Revival characteristics popular in the 1920s. Homes built at that time in many Rochester neighborhoods had deed stipulations preventing African Americans from living there. It’s likely that Arvine’s middle-class neighborhoods were among them, and I’m going to dig a little more to find out. “Restricted” was the code word used to describe this discriminating practice. It was not illegal, but it has had terrible repercussions for the Rochester region that continue to this day. I don’t know, yet, how Arvine became the contractor for the house I lived in. Did she know the Blackalls, the family who had it built? Did she have an arrangement with Ellwanger & Barry Realty Co., which was developing the area? Arvine retired in 1929. When she died in 1934 she left an estate of $10,000, about $180,000 in today’s dollars. Half of it went to her niece, Sarah Caldwell, and the other half went to her longtime housekeeper, Sadie MacPhee. By the way, years after I learned about Arvine I just happened upon her grave on one of my walks in Mount Hope. She is buried next to her husband and her parents. Sources: City of Rochester Historic Resources Survey 2000, cityofrochester.gov Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, 18 Jan 1934, fultonhistory.com  I spent some time researching my Sicilian ancestors today. This is my grandmother, Sara Mazza Parker, my namesake. Born in 1907, first-generation. A teacher saw her potential and encouraged Grandma's old-country parents to let her go to college. She was a Cornell and Middlebury graduate, master's degree, teacher. We can say it's the classic American immigrant success story. But we can't forget the other classic American story: immigrants as dirty, dangerous, ignorant. This has always been with us. I learned 11 Sicilians were lynched in New Orleans on one gruesome March day in 1891. There were many more incidents of violence and exclusion in cities where Sicilians settled. Italians from the mainland distanced themselves from the poor, illiterate peasants from Sicily. My great-grandfather knew no English of course when he came to the States on April 4, 1904. He was a fisherman from Brucoli. He settled in Oakfield, Genesee County, New York, joining his older brother, Sebastiano, and worked in the gypsum mines. He sent for his wife, Maria Bucceri Mazza, from Sortino, a few years later. She came with their two young children, my grandmother's older sister Francesca and brother Pietro (Aunt Fran and Uncle Peter to me). It would be generations before Sicilians found their place in mainstream American society. My grandma would have grown up hearing those stories. No wonder she changed her name from Santina to Sara and married a Yankee. That is a story for another day. I wish I'd asked more about her early life when she was alive. I would have asked her about this.  If Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ name sounds familiar, it’s probably because she wrote The Yearling, the 1938 classic bestseller that earned her the Pulitzer Prize in 1939 and became a movie starring Gregory Peck in 1946. But before she was a famous novel writer, Kinnan Rawlings was a newspaper reporter in Rochester. She was a features writer at the Journal American, a Hearst newspaper whose salacious approach to the news was considered a bit scandalous, though deliciously titillating, in conservative Rochester. Owner J. Randolph Hearst liked to shake things up and make a splash, and he did so in Rochester. Their offices were at 128 St. Paul Street, at the corner of Andrews. You can still see the marquis over the door. (Side note: Cook Iron Store moved into the space in the 1930s, shortly after the paper folded, and has been there ever since.) Before the world read Kinnan Rawlings’ books, women were reading her poetry. She wrote a column of light verse after she joined the staff at the Times Union, one of two Gannett newspapers in Rochester. Poetry, by men and women, was a regular feature in newspapers at the time. “Songs of a Housewife” ran six days a week for a couple of years and became so popular it was syndicated to 50 newspapers around the country. Her reflections on daily life for American women appeared just a few years after women had finally won the right to vote. In her twenties and coming into her own when she wrote them, Kinnan Rawlings tapped into a new sense of freedom and possibility that women were feeling at the time. By the late 1920s, Marjorie and her husband, Charles, both journalists, were feeling restless in Rochester. They took a leap and bought a 72-acre farm in frontier Florida. Their new home provided a rich setting for her books to come. But her time in Rochester was an important part of her growth as a writer. Her columns are an early peek at Kinnan Rawlings’ writing style and voice, and they reveal a lot about American popular culture. They were largely forgotten until the 1990s, when researchers resurrected them and published about half of them in Poems by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings: Songs of a Housewife. Photo: State Archives of Florida  Fresh from the ‘Rochester Writers Who Found Fame’ file: Mary Jane Holmes – No, her name doesn’t ring a bell. But she was a bestselling and prolific writer (39 popular novels as well as short stories, magazine series and novellas) in the late 1800s. She lived in Brockport from 1852 to 1907. She sold 2 million books in her lifetime, second only to Harriet Beecher Stowe, and wrote about gender roles, race, class, slavery and war. None other than ‘The Nation’ published her obituary: “It is an eternal paradox of our world of letters that the books which enjoy the largest sale are barely recognized as existing by the guardians of literary tradition. Mrs. Mary Jane Holmes, who died Sunday at Brockport, N.Y., wrote thirty-nine novels with aggregate sales, it is said, of more than two million copies, and yet she had not even a paragraph devoted to her life and works in the histories of American Literature.” Photo: ca. 1865, SUNY Brockport / Emily Knapp Museum, Brockport NY Found Frank today! Burton Francis (Frank) Blackall was the dad in the Blackall family. He’s been hiding from me in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester. I knew what area he was buried in, but his headstone has eluded me for years. Early on, Frank used his position as a telegraph operator to support Frederick. In 1859, the abolitionist was out of town when he learned officials were looking for him in connection with John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. Frederick sent a telegram to Frank, then 26 years old, “a friend and frequent visitor at my house, who would readily understand the meaning of the dispatch: ‘B.F. Blackall, Esq., Tell Lewis (my oldest son) to secure all the important papers in my high desk,’” he wrote in his third autobiography. “I did not sign my name, and the result showed that I had rightly judged that Mr. Blackall would understand and promptly attend to the request.” Frank and Frederick had a long friendship, even after Douglass moved to D.C. Photo by Gia Lioi Originally published 10/20/2013 When Frederick Douglass moved from Rochester, NY, to Washington, DC, in 1872, he left behind a lot of friends and supporters. But he didn’t lose touch. In fact, his moving away means we can see the nature of those relationships more clearly through the letters he exchanged with them.

Frederick and his second wife, Helen Pitts Douglass, corresponded with the Blackalls for many years. For the most part they are cordial and chatty letters about everyday life - the weather, the health of family members, invitations to visit. They describe family gatherings - Fred playing violin with his grandson, the Blackalls vacationing on Frontenac Island on the St. Lawrence River. Some highlight big events, like the Chicago World’s Fair and President Garfield’s election, and others comment on the politics of the day. Most of the letters between Burton F. (Frank) Blackall and Frederick were about business; Frank looked after rental properties that Frederick owned back in Rochester. Little has been written about Douglass the real estate investor, but he owned a fair number of properties. With these letters, it’s more than just his name on a plat map or deed. They show the typical wranglings of being a landlord - finding good tenants, fixing old pipes, collecting overdue rent. So far the letters I’ve tracked down are from Frank to Fred and show the mild frustration Frank went through being the go-between: “I have held this money for several days in hopes that I could collect the rent due you from the Bond Street property and remit that also, but I am sadly disappointed as I know you will be also,” Frank wrote on Sept. 29, 1877. “The truth of it is that the tenant is a ‘dead beat.’ We will never be able to collect a cent from him. He is all packed up and ready to move out. The sooner he goes, the better.” Some things never change. I’ll write lots more on all the great letters I’ve found! Originally published 9/27/2012 Filed under frederick douglass rochester ny Helen Pitts Douglass Blackall

|

Details

AuthorThese are stories of people, places and events of the past that seem to jump out at me. Maybe they've been waiting for someone to tell them! Archives

July 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed